“As a kid, you think you’re the only one who feels so strange, so out-of-kilter with what seems to be expected of you. Then, with luck, you meet your tribe, the other ones who grew up feeling just as weird, and that’s who I write about.”

Date of Birth: November 10, 1960.

I was born and grew up in New York. New York is a powerful presence in my work—the grimy, anarchic city of my childhood that got gradually botoxed into a mall simulating the urban experience.

So are misfits.

As a kid, you think you’re the only one who feels so strange, so out-of-kilter with what seems to be expected of you. Then, with luck, you meet your tribe, the other ones who grew up feeling just as weird, and that’s who I write about. In both my novels and my non-fiction, I’ve explored painful difference.

What’s it like to be Isaac Hooker, hero of my novel Isaac and His Devils, a half-blind half-deaf overweight genius growing up in backwoods New Hampshire, who goes to Harvard on scholarship but finds himself too paralyzed by his own ambitions not to self-sabotage?

What’s it like to be French countertenor Philippe Jaroussky, a handsome clever ambitious musician from the comfortable Paris suburbs who feels compelled to hike his voice high enough to sing parts written for 18th century castrati?

BITE YOUR FRIENDS

“I Bite My Friends to Cure Them”—Diogenes of Sinope, 3rd Century BC

In 2018, I published a memoir in Granta and in Lithub about my friendship in the 1970s with performance artist Stephen Varble. This memoir formed the basis of BITE YOUR FRIENDS: STORIES OF THE BODY MILITANT (2024), my book about the body as a site of resistance to power.

I first met Stephen at the Easter Day Parade when he was wearing a dress made of gold Scotch labels, matchsticks, and a miniature matador-and-bull. I was a gawky fourteen-year-old, he was twenty-eight. I was carrying his photograph in my wallet. For three years, Stephen was my best friend and, weirdly enough, my protector. Through him, I met people like Peter Hujar, his sometime lover, who took some of most sublime photographs of Stephen’s guerrilla performances.

Stephen and I wandered the city together, from Hungarian teashops in Yorkville to the leather bars of the West Side Highway. Even when we got ambushed in the meat-packing district by a white gang carrying broken bottles, I felt safe with Stephen: he was the first person I knew who seemed to be scared of nothing--except being ignored.

Stephen died of AIDS in 1984. For years, he was forgotten, but now his artistic practice and guerrilla performances are becoming crucial to a new generation using their own mutating bodies as sites of playful protest.

Stephen Varble is one of the heroes of BITE YOUR FRIENDS: STORIES OF THE BODY MILITANT—a history-memoir that features saints, philosophers, prophets and rebel artists from Diogenes to Pussy Riot, along with the running story of me and my mother.

STubborn Loners

Some of the people I write about are stubborn loners isolated by the freakiness of their artistic vision, but others have been marginalized by their skin-color or clothes or accent.

For six years, I lived outside Perpignan, a southern French city with supposedly the largest settled Rom population in Western Europe. In 2000, I started writing about Moise Espinas, a musician in the Gypsy band Tekameli, and his wife Diane. (This project became Little Money Street) The Rom community in Perpignan still lives by pre-modern codes of honor and hospitality, of female chastity and pit-bull-style hyper-masculinity--codes of a warrior elite that were once part of our own ancestral DNA, but that today survive mainly among the disenfranchised.

My relationship with Diane and her family has deepened over the years into an unexpectedly fierce love: Diane calls me “Maman”; I’m godmother to her son Kevin who is by now married with two kids of his own. More than once, Diane and I have saved each other’s skin. Being her second “Maman” has meant entering a network of clans and neighborhoods where nobody is ever alone, but whose members are treated as toxic by mainstream France. Being friends with Diane has meant losing my own rich-white-lady assumptions that the world is a friendly open place, and seeing what it’s like to have waiters in a café refuse to serve you, or strangers snatch their children out of your sight.

Family

““From my grandfather, I grew up thinking of the English language as this great saltwater-taffy voodoo doll that can stand a lot of teasing and contorting.” ”

My other ruling subject is family, whether I’m writing about a teen runaway in search of the father she’s never met in my novel RAT or about the Sicilian nobility in my New Yorker piece about Lampedusa and "The Leopard."

I’m fascinated by how children try to escape family patterns to forge their own destinies and find their own people, and how they make their way home again.

My own family story, it seems to me, illustrates a particular 20th century American trajectory.

My father’s father, Ferdinand Eberstadt, was a Wall Street banker who was active in government during World War II.

Son of two ambitious immigrants—Venezuelan mother, German Jewish father--Ferdinand made himself firmly part of the WASP power establishment.

My father Frederick who loved Europe, avant-garde theatre, high society, bucked his family’s expectations by dropping out of Princeton and becoming a fashion photographer. Then, at the age of 65, one more brave and timely reinvention: he went back to college, got his MSW, and set up shop as a cognitive behavioural therapist.

My mother, the late Isabel Nash Eberstadt, was the daughter of the poet Ogden Nash. She became a society beauty who wore outrageously stylish Paris couture, a patroness of the avant-garde whose great loves were underground filmmaker Jack Smith, Andy Warhol, theatre director Robert Wilson, playwright Adrienne Kennedy.

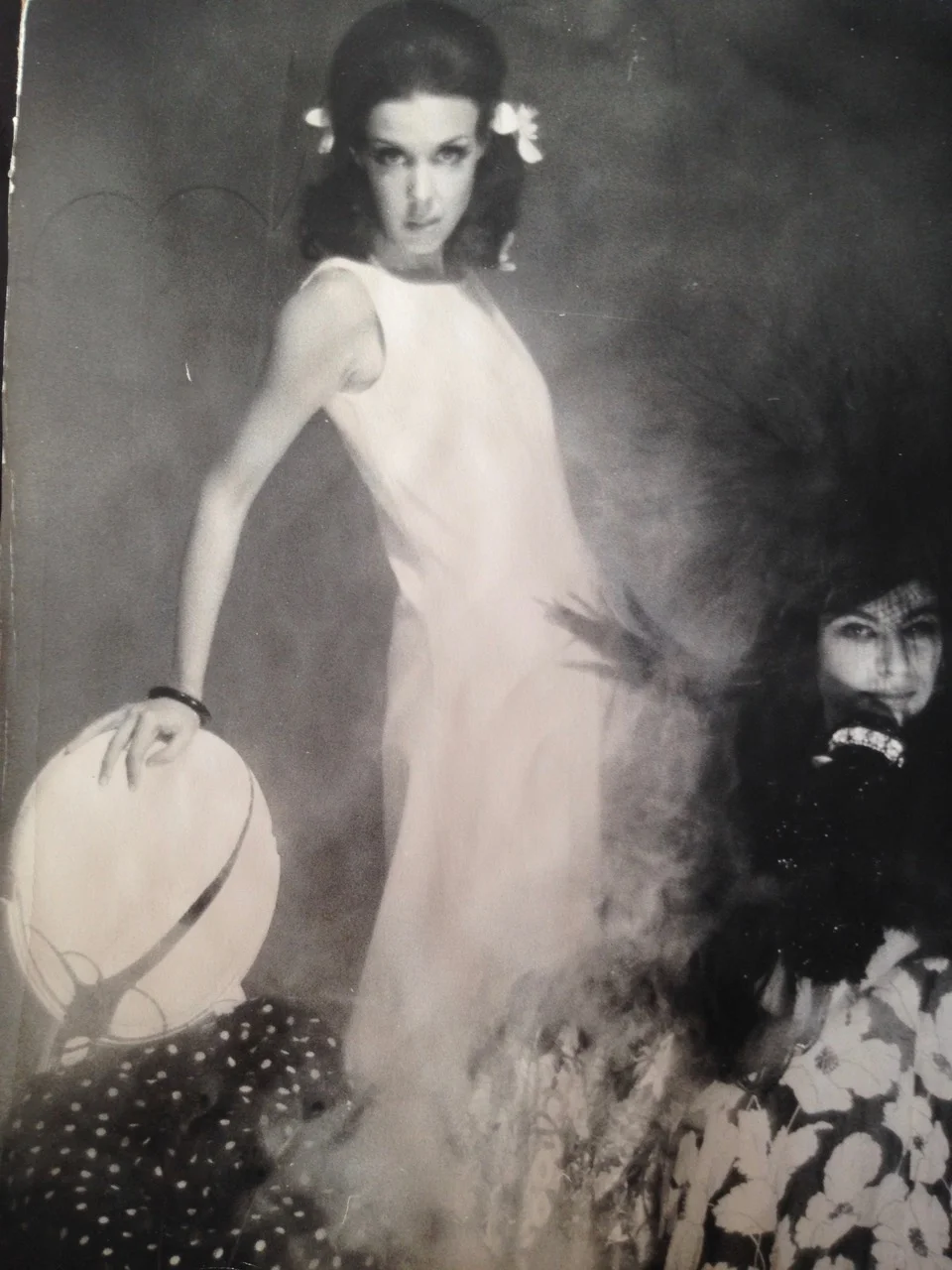

(Photo of Isabel Eberstadt by Jack Smith, with actor Mario Montez)

But all she ever wanted to do was be a writer: she published two novels 25 years apart. My mother battled with lifelong manic-depression, although the manic jags dimmed down with age, and the depressions got duller and more lingering.

My upbringing was intensely privileged, and also scarily chaotic.

This photograph of me, aged 3, was taken in Central Park in 1963 by Diane Arbus.

New York in 60s and 70s

I went to Brearley, an Upper East Side private girls’ school, but cut school to watch underground movies at the Anthology Film Archives with my mother. Or sometimes just to write the daily journals I’ve kept since I was fourteen.

Growing up, I felt like a freak, unable to grasp the most basic rules of life. Writing was the only place anything made sense to me.

This is still true.

The year I was sixteen, I worked at Andy Warhol’s Factory, writing pieces for “Interview” and answering the phone. It was the most thrilling time of my life—maybe a little too thrilling. (I am working on a book about this period of New York in the 70s that will be part-memoir, part-raw diary.)

The following year, I bullied my school into allowing me, despite lousy grades, to go to London to cram for the Oxford entrance exams. I needed badly to get away from home. Reading English at Oxford had been my long-time dream, a necessary step, I believed, in becoming a serious writer.

I lodged in a series of rackety London boarding houses, and scraped through the entrance exams: I was one of the first women accepted by Magdalen College. At Oxford, I learned how to work hard. In 1982, I graduated with a Double First Class Degree in English, tied for top place in my year.

That first year out of college was the scariest time in my life. The prospect of entering the real world--and risking failure--felt totally crushing.

After graduation, I moved back to my parents’ apartment in New York, locked myself in my childhood bedroom, took way too many drugs, and tried to write a novel that eventually became Low Tide.

It was the early 1980s, the Reagan years. My old friends were coming down with hepatitis C, dying of AIDs. New York was going through its Gilded Age clearances, tenements and welfare hotels were being gentrified into safe space for yuppies (a word that had just been invented). The West Side piers that I’d frequented with Stephen Varble were being razed.

I had been a precocious kid with excellent family connections, but I was terrified by my own capacity for self-destruction.

In 1983, my older brother, then a Harvard demographer, let me tag along on a research trip across the old Soviet Union. Six weeks in Russia turned me into a Cold War-style anti-communist. Back in New York, I found the moral certainty I was longing for among neoconservatives who inveighed against the permissive 60s liberalism that had been my mother’s milk. I went from being an apolitical Episcopalian to being a would-be-Jewish right-winger, studying the Hebrew Bible under a brilliant rabbi who taught night classes to Orthodox women.

Today, when I've talked to French kids--the children of secular North African immigrants--who've converted to hard-core Islam, I so recognize that feeling of ecstatic rage and righteousness, the whole of world history flaming into focus.

During those six years, I published a series of jeremiads against left-leaning novelists—including what’s been described by one critic as an “infamous spitball” against the Italian writer Primo Levi, which thirty-odd-years later I still bitterly regret. I was 24 years old, ignorant and self-divided. Privilege hadn’t given me much humanity or self-knowledge.

When the spell wore off, I moved back to Europe and tried to start from ideological scratch, feeling that all my loud convictions had been worse than wrong.

A mute and hollowed-out place for a writer to write from…

In 1993, I married the British writer Alastair Bruton who was then based in Paris, and buried my self-dreads in the joyous all-consuming bustle of birthing and raising two children. Maud, born 1995. Theodore, born 1998.

Since the late 90s, I—we—have been living in Europe.

““It’s simpler, feeling like a Martian in a place where you speak the language badly than in your own hometown. Most writers, me among them, are itinerant preachers, ranting at a house that’s long been boarded up. Home is a suitcase full of amulets too secret and painful to unpack.””

““Fernanda Eberstadt is blessed with more gifts than any one writer should be. She saturates her novels with wantonly vivid images, creates characters more thoroughly realized than most people you know, swings from yuppie jive to epigrammatic eloquence without losing her balance, and seems to know everything about everything, from the Old Testament to the coffee shops of Madison Avenue. Her prose is exuberantly, obscenely rich.” ”